Evaluating value for money in public services is a tricky business

As consumers, we are constantly making judgements about value for money (VfM). When we make a decision to purchase something, that’s presumably because we feel it is going to be ‘worth it’ in some way. We don’t always judge things correctly; with the benefit of hindsight, some things turn out to have been well worth it (our expectations fulfilled), others less so.

The bigger the purchase, the more carefully we look at VfM. When our finances get tighter, that can also force us to think harder about how valuable or important something is, and whether it’s worth buying. And that’s just as true for business and government as it is for households.

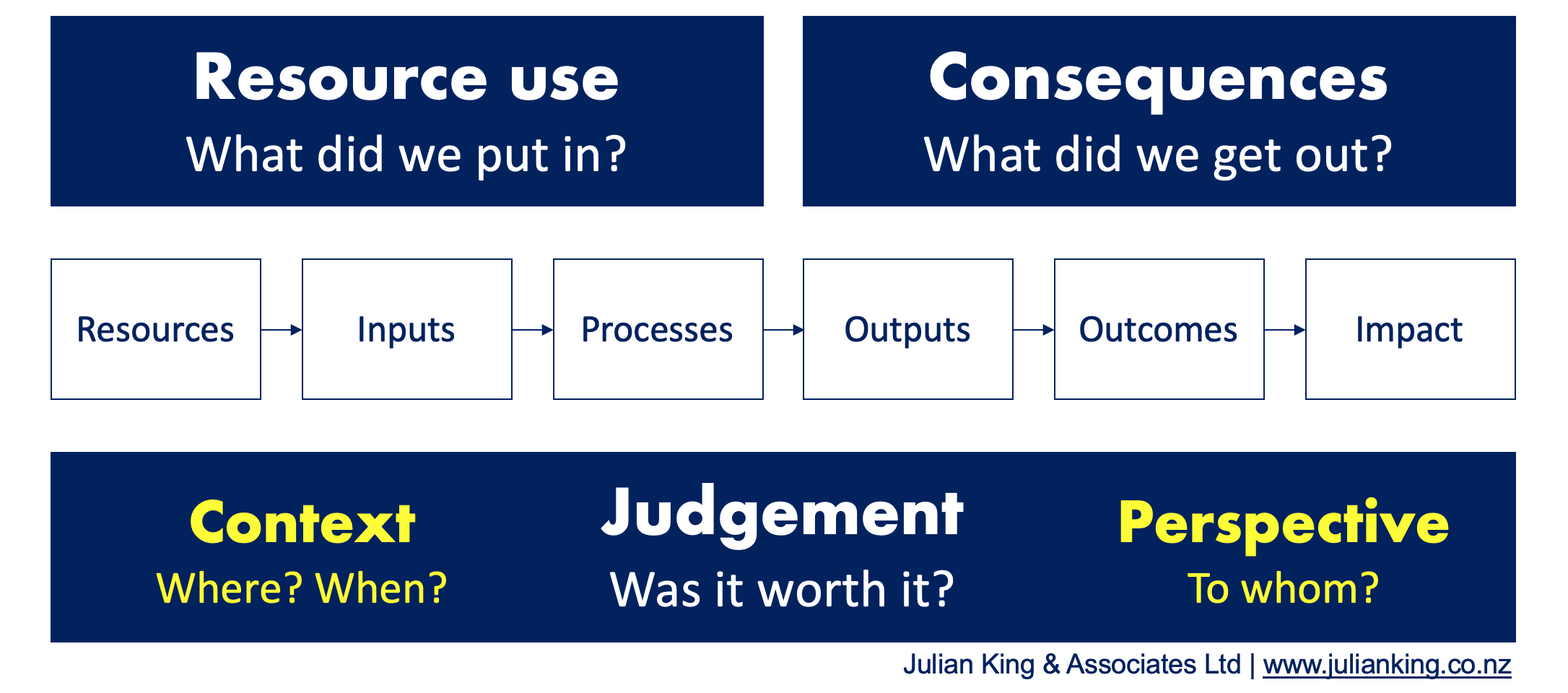

Any investment, no matter how simple or complex, can be evaluated by addressing three questions: What did we put in? What did we get out? Was it worth it?

One form of VfM evaluation is to calculate return on investment. For a business, this might be as simple as ‘how much money did I invest, how much did I make from it, and was that enough compensate me for the effort and risk involved?’

But life isn’t always that simple, and we could add layers of complexity to this – for example, our business investment might have ethical, social and/or environmental impacts (positive or negative) and those impacts might cause us to modify our assessment of whether the investment is worthwhile.

What constitutes “worth it” is a matter of context and perspective, and requires a judgement to be made, on the basis of credible evidence, explicit values, and logical argument.

When a government is spending public funds in social change, judging worth can be a complex matter. For example:

- The people spending the money and the people who are supposed to benefit are different groups, and we cannot take for granted that their values are aligned.

- The primary reason for investing is typically not to make a profit, but to change people’s lives. These sorts of outcomes are often broad and multi-faceted. If we want to evaluate them we are faced with a balancing act: describe them in clear, simple terms and risk being ‘too narrow’ and missing something important; or, provide a richer description and risk being ‘too woolly’ without a clear outcome to measure.

- The outcomes we’re looking for usually go beyond things we can count – they are also about quality, value and importance – from the perspectives of a diverse range of people.

- There may be trade-offs – e.g., if we spend more money to help one group in society, we might have to spend less on another group.

- There may be unintended, unanticipated impacts that fundamentally alter the value of the investment.

Economic methods of evaluation can help us to navigate these complexities in a systematic, rational way. Using cost-benefit analysis (CBA), for example, we can identify the costs and consequences of an investment, quantify them, and value them in monetary units. We can take into account the different timing of costs and benefits, and compare results with the next-best alternative use of resources. We can apply forecasting and modelling techniques to explore future value and understand the role of uncertainty and risk in the investment. Crucially, the results of a CBA can tell us whether an investment makes people better or worse off in aggregate.

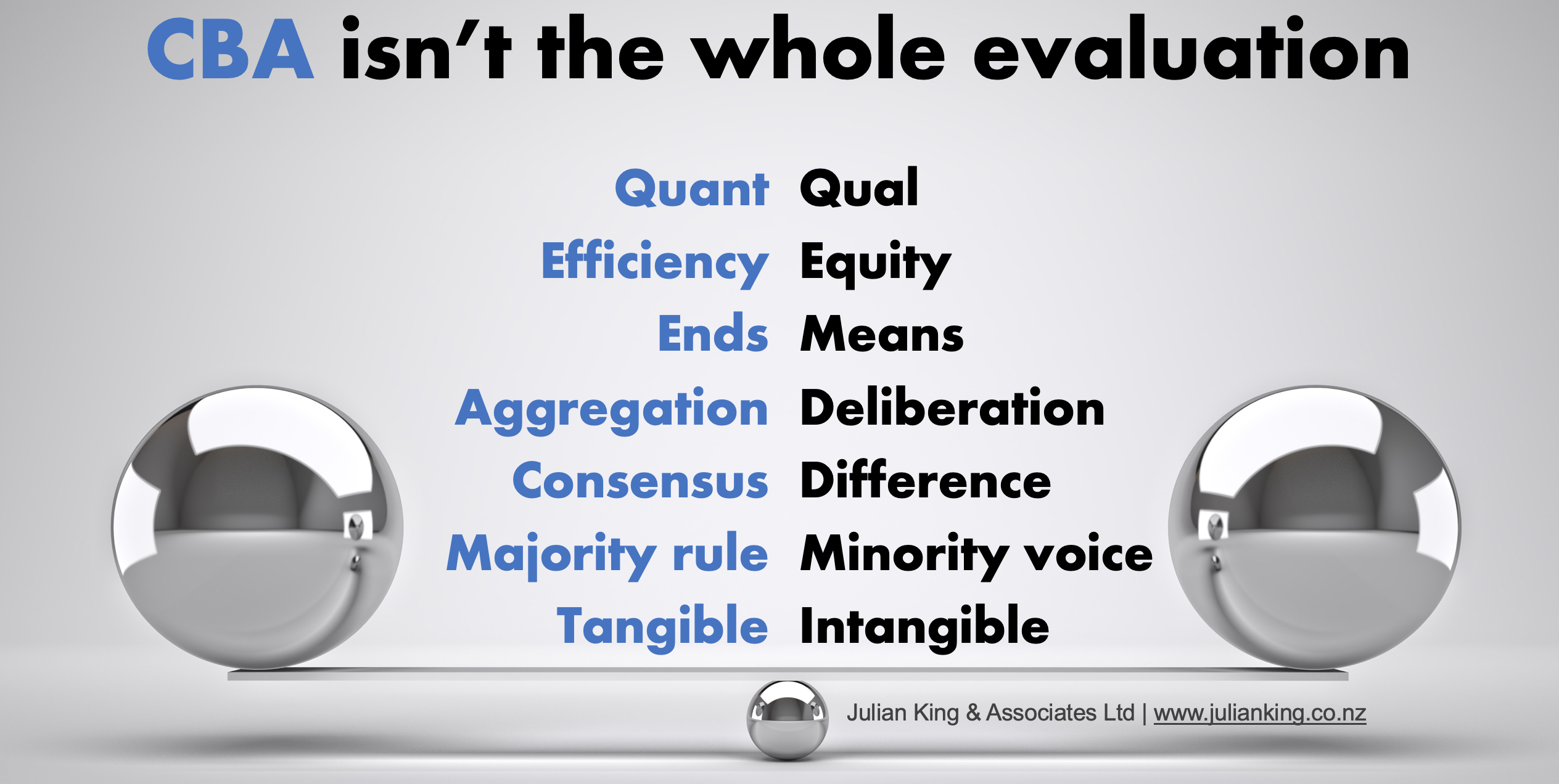

There are also things CBA can’t tell us, which might be important in determining whether something is worth investing in. We might want to know not only whether society is better off overall, but who within society is better or worse off. The most efficient investments might not be the most equitable ones. If we want an intervention to reach the most disadvantaged, there may be extra costs. We might want our evaluation to make these trade-offs explicit.

If a policy intervention involves understanding and balancing the interests and values of different groups, we might need methods that can deal with these differences openly and transparently, rather than valuing everything in the same units and aggregating. Differences in group size, socioeconomic status, political power, and other factors, sometimes need to be made visible in an evaluation.

Evaluating resource allocation requires evidence about performance (‘what works’) and evidence about values (‘what matters’). It requires a mix of technical and social inputs, and a blend of individual, collective, and systemic thinking. If we limit the analysis to return on investment, we run the risk of privileging some types of evidence and values over others: quantitative over qualitative; efficiency over equity; ends over means; aggregation over deliberation; consensus over difference; majority rule over minority voice; tangible over intangible values.

Economic evaluation has great capacity to inform good decisions, provided it is used to serve sound reasoning, not replace it. For this reason, we often recommend that economic evaluation is treated as a part of an evaluation, not the whole evaluation.

Economic evaluation can be combined with other ways of analysing evidence and judging value. The Value for Investment approach uses rubrics and mixed methods to evaluate VfM. It provides a robust way to integrate economic evaluation with wider criteria and evidence. The approach is rigorous, systematic, intuitive to use, and offers flexibility to support nuanced and context-sensitive judgements about VfM that respond to stakeholder needs and values.

March 2019