A Value for Investment report deconstructed

This social and economic impact assessment for the UN’s International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) demonstrates the Value for Investment system in action:

- It combines theory and practice from evaluation and economics.

- It uses mixed methods evidence (quantitative and qualitative together).

- It uses evaluative reasoning (assisted by rubrics) as the backbone for evaluation design, synthesis, and reporting.

- It engaged stakeholders in evaluation co-design, fact-finding, and sense-making.

In this post I will deconstruct the following report to illustrate how we followed a sequence of 8 steps to provide succinct findings, backed by evidence and reasoning.

The report presents findings from a social and economic impact assessment of a long-term scientific collaboration between 22 countries, supported by the IAEA’s Technical Cooperation programme. The collaboration goes by the acronym “RCA”, which stands for Regional Cooperative Agreement for Research, Development and Training Related to Nuclear Science and Technology for Asia and the Pacific.

We completed three impact assessments for the IAEA (links to all three reports are provided at the end of this post). The one featured here focused on non-destructive testing, a set of nuclear techniques used in industries such as shipping, construction, aerospace, manufacturing, etc, to evaluate the integrity and properties of materials or components without causing damage to the tested object. We found that the 22-country collaboration has contributed to strengthening non-destructive testing capacity and capability over the past 20 years. It has increased demand for and use of non-destructive testing, leading to improved health and safety, and creating economic value.

We used the VfI approach

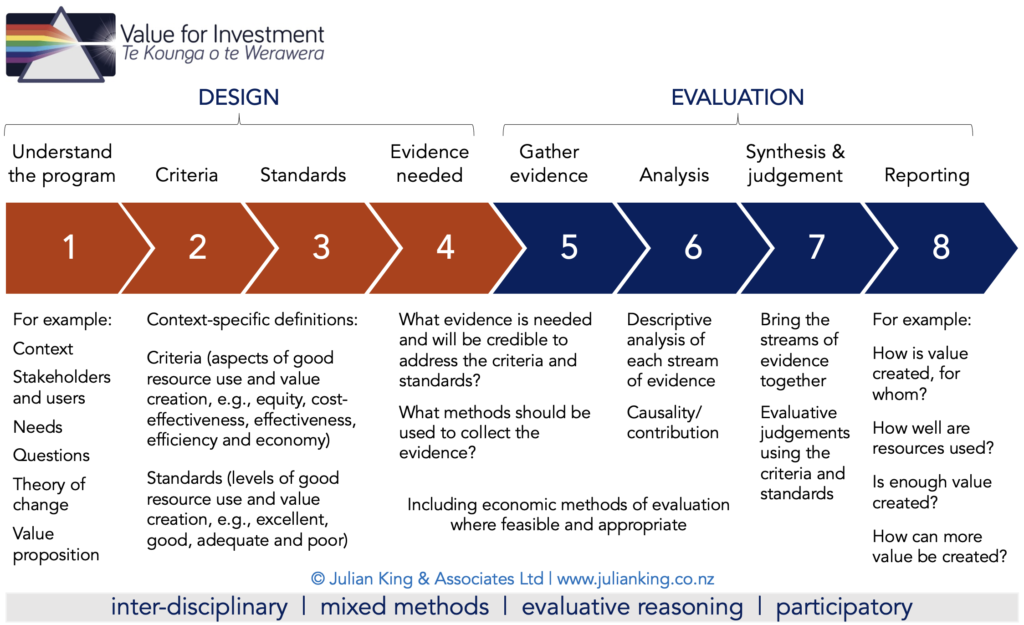

To design and undertake the impact assessment, we followed a sequence of 8 steps, as shown in the diagram below. Following these steps helped to ensure the impact assessment was aligned with the programme design and context, gathered and analysed the right evidence, interpreted the evidence on an agreed basis, and provided clear evaluative judgements based on robust evidence and sound reasoning.

This process, which can be used in any evaluation, is designed to be inclusive and collaborative. Each step is an opportunity to involve stakeholders, supporting understanding, ownership, validity, and use.

The impact assessment was conducted during a global pandemic and all of the steps were completed remotely, using email, videoconferencing, file sharing, and survey software.

Step 1: Understand the program

First we invested time to orient ourselves to the program and its context. What is non-destructive testing? What is the RCA? Who are the stakeholders? Who needed this impact assessment, and why? We had to do our homework to find out.

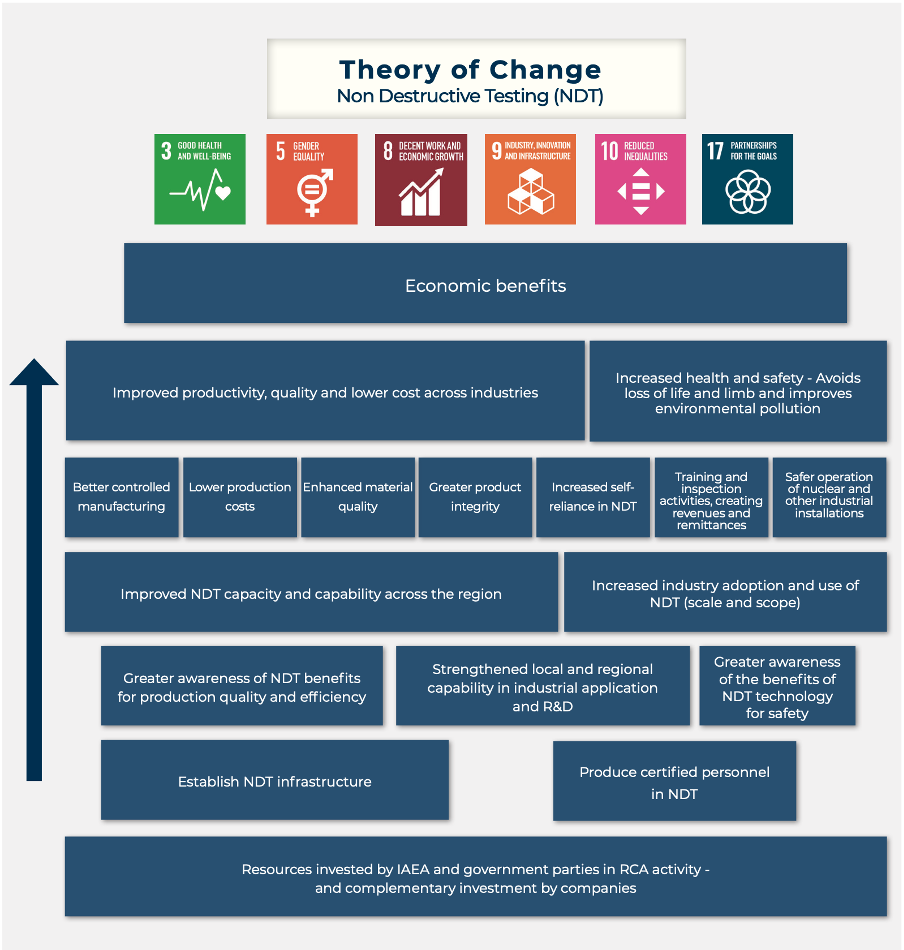

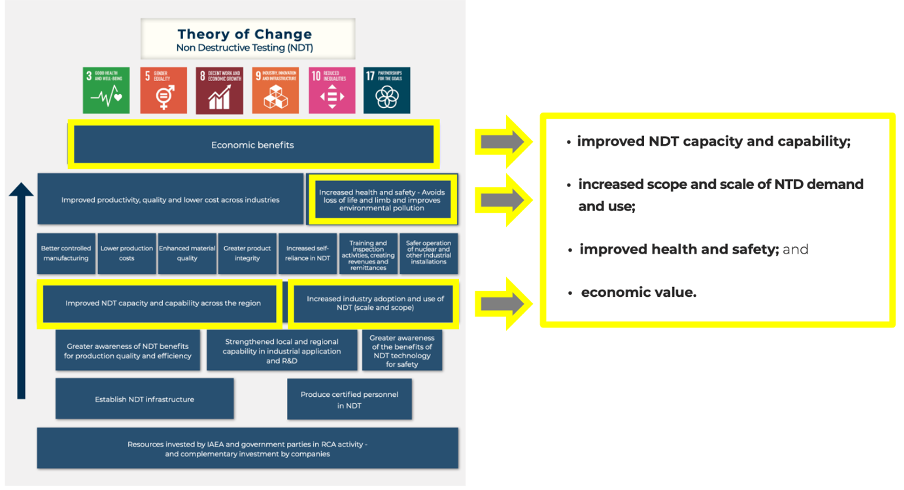

Then, we worked with expert stakeholders to develop a theory of change. Here it is. It might look simple but multiple versions of this diagram circumnavigated the globe via satellite and undersea cable to reach this agreed version.

Step 2: Identify criteria

Criteria are aspects of performance. Here, we identified four aspects of social and economic impacts, aligned with the theory of change.

This report aptly illustrates the point that the VFI system does not prescribe any particular set of criteria such as the 5Es (economy, efficiency, effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and equity). Criteria are contextually determined.

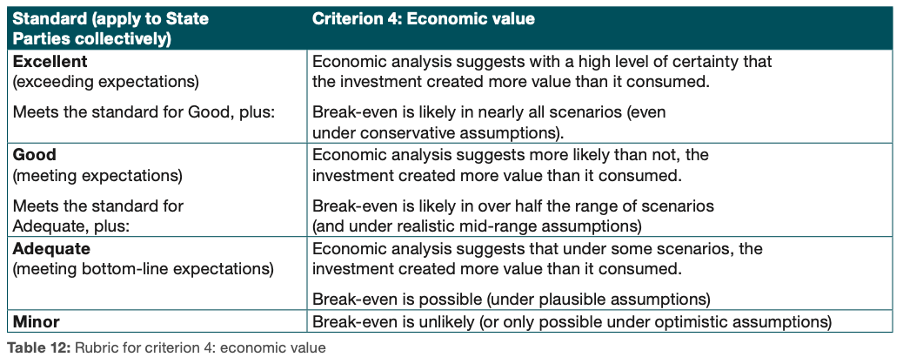

Step 3: Develop standards

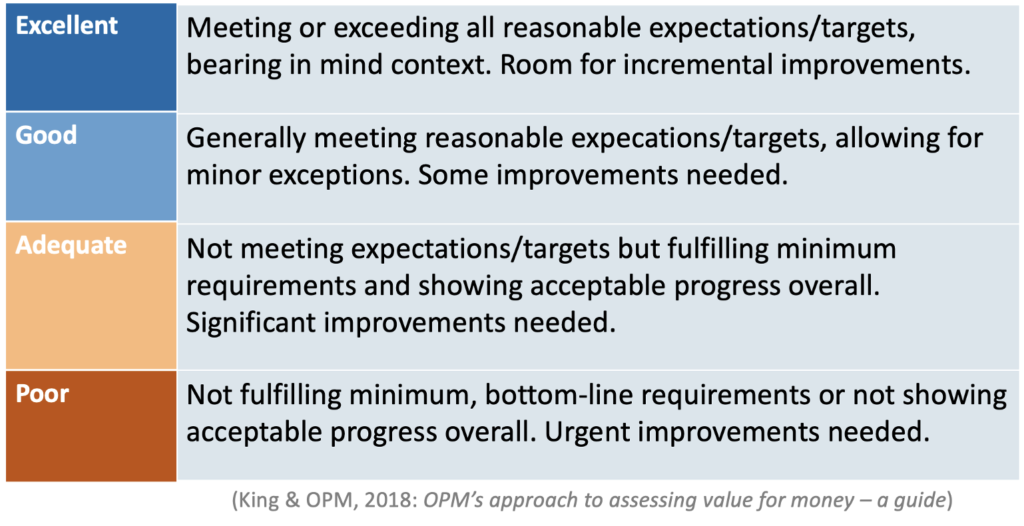

Standards are levels of performance. Here’s a generic set of definitions we often use to define what excellent, good, adequate and poor performance mean. When we’re developing program-specific definitions, we calibrate them to these generic definitions.

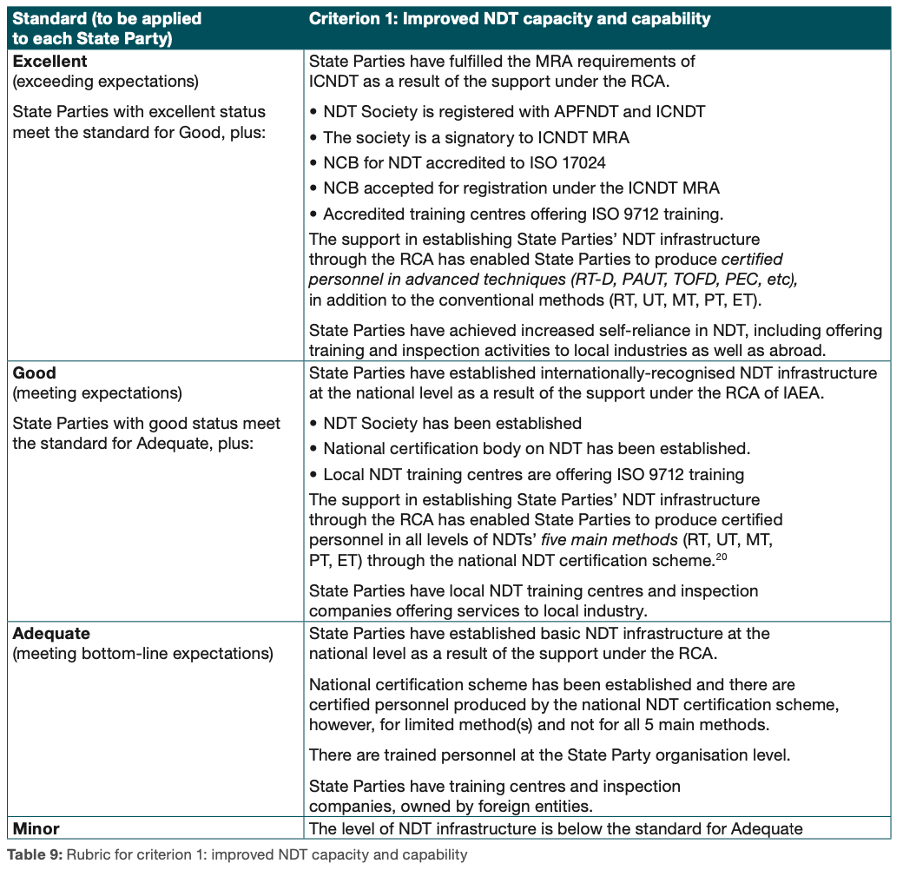

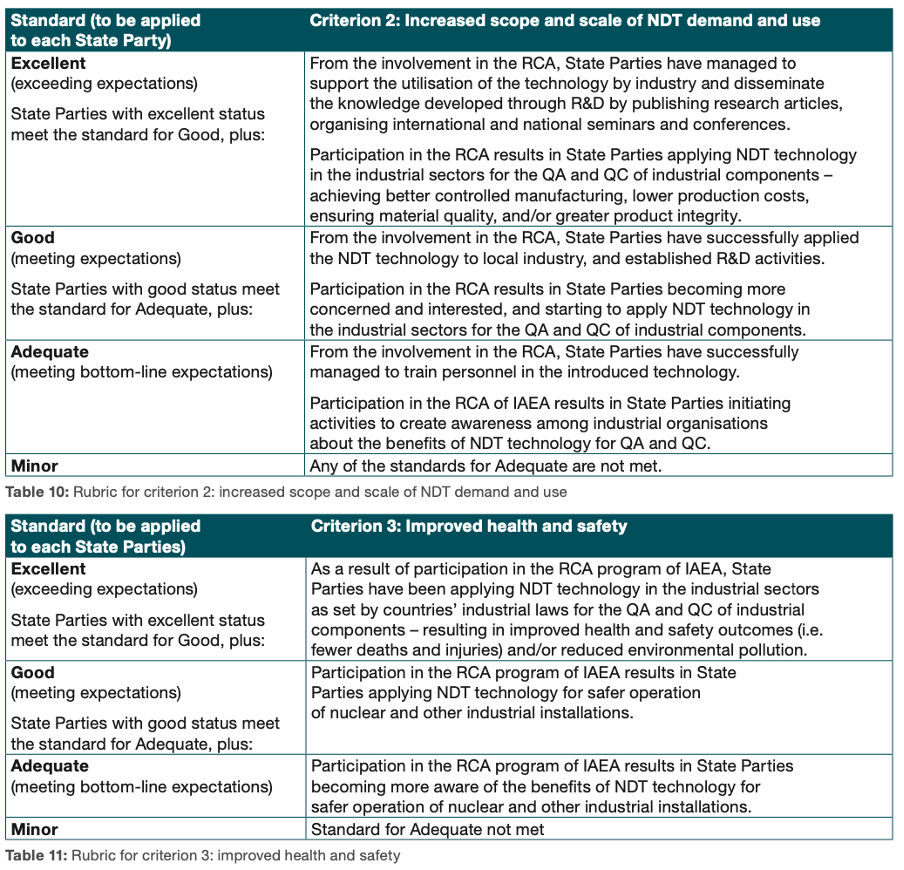

A rubric is a matrix of criteria and standards. For this impact assessment we co-developed four rubrics – one for each of the overarching criteria identified in step 2 above. Each rubric articulated sub-criteria describing what the evidence would look like at each level of performance.

Co-designing rubrics remotely is an interesting process. I estimate draft rubrics travelled 213,000 km (as electrons) before they were finalised!

These rubrics are the backbone of the whole evaluation. Developing rubrics brings stakeholders to the table (albeit in this case, a metaphorical table) to discuss what matters (criteria), and what good looks like (standards). The rubrics articulate a shared and agreed understanding of how evaluative judgements should be made from the evidence. They delineate the scope of the evaluation and help to clarify what evidence needs to be collected. They provide a framework for organising the evidence so it is efficient to analyse. They provide a set of lenses for making sense of the evidence. They also suggest a structure for reporting findings, based on the aspects of performance that matter.

Step 4: Determine evidence needed

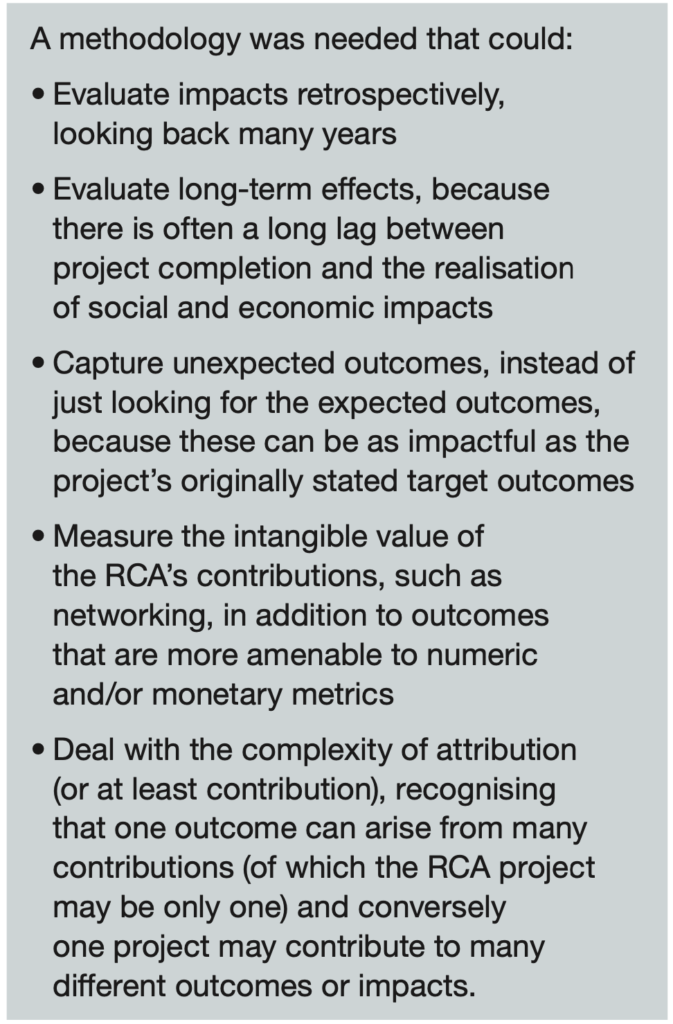

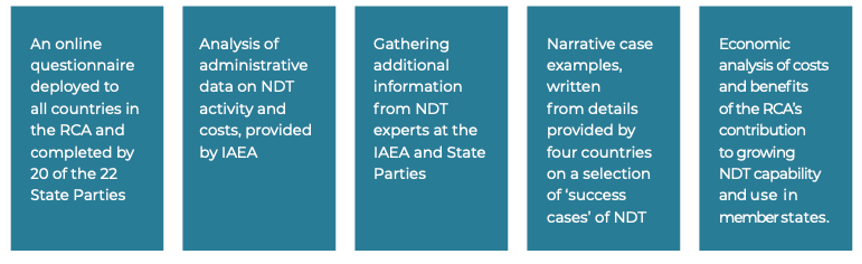

A challenge in this impact assessment was that it needed to look back 20 years and estimate social and economic impacts without access to routinely collected impact data, and with only a hypothetical counterfactual. This required some detective work, using a carefully selected mix of methods.

One of the useful things about rubrics is that they bring clarity about what evidence we need to gather, and they help to drive focused conversations about how to gather it. We could see from the rubrics that a mix of quantitative and qualitative evidence would be needed. We agreed on five sets of methods:

The detailed design of each method was explicitly aligned with the rubrics. For example, the content and structure of the survey and case examples systematically addressed the concepts set out in the rubrics.

Step 5: Gather evidence

We designed and implemented an online survey, narrative case examples for four of the countries, online interviews/email correspondence with scientific experts, and data requests for administrative and cost data held by IAEA. Each strand of evidence was gathered by a different member of the team.

Step 6: Analyse evidence

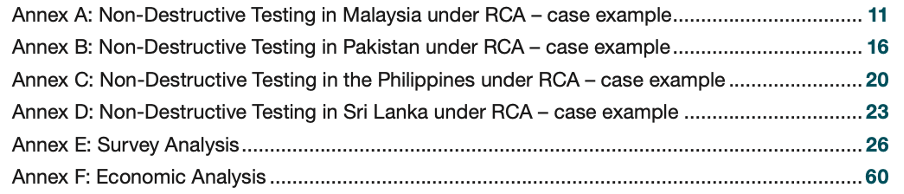

Each strand of evidence was analysed and written up into a series of Annexes for the report. The analysis was aligned and structured according to the criteria (for example, the survey had separate sections for improved NDT capacity and capability, increased scope and scale of NDT demand and use, and improved health and safety).

The Annexes give a detailed account of the facts and figures we gathered, but they don’t provide evaluative conclusions – that is, they don’t give a judgement of how good the impacts were. That happens at the next step.

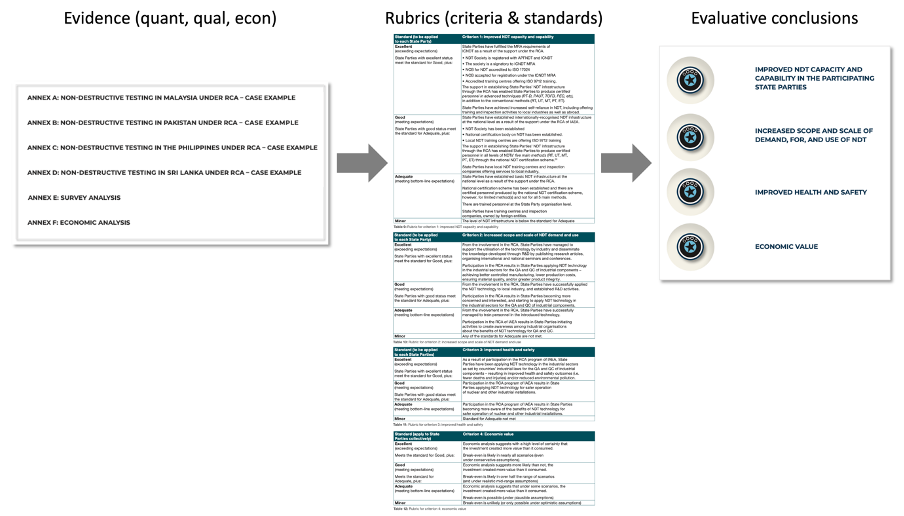

Step 7: Synthesis and evaluative judgements

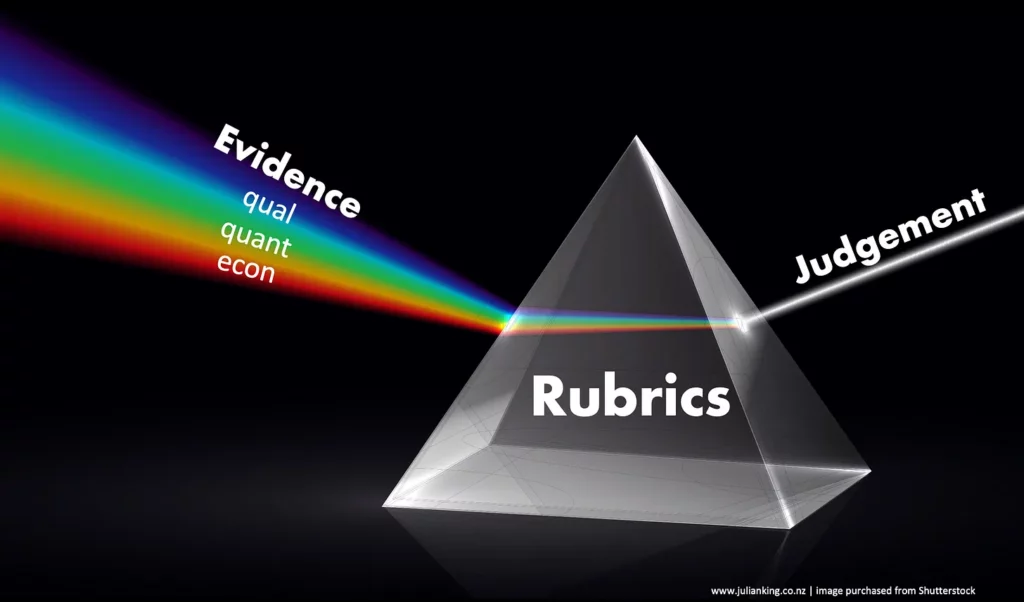

This is where we get from the evidence (set out in Annexes) to evaluative judgements about the social and economic impacts. The criteria and standards give us a shared set of lenses for looking at the evidence and making those judgements on an agreed basis.

Metaphorically speaking I think of it like a prism, except in reverse: we can feed in a whole spectrum of evidence – quantitative, qualitative, and economic – and use the prism of the criteria and standards to bring it all together and reach a sound, transparent, traceable evaluative judgement.

Of course, in real life we don’t get to use a prism. The following diagram is closer to reality but the prism metaphor illustrates the purpose behind all the tiny words below. According to the evidence, the programme met the agreed standards for good performance on all four criteria.

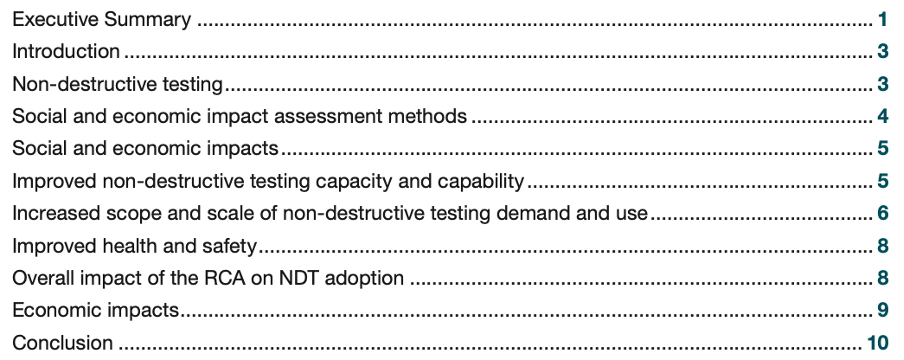

Step 8: Reporting

Now comes the time to communicate what we found. The rubrics can help with this step too.

A good evaluation report gets straight to the point and gives a clear statement of the findings, right up front. The reader should be able to get the so what in a minute or two, without searching for it. After that, the rest of the report can unpack a more detailed story of what the evidence shows and how we reached our conclusions.

That’s exactly what we did here. By the time you’re done reading pages 1-2, you’ll know what the headline impacts were and how good they were judged to be. By the time you get to page 10, you’ve finished reading the evaluation report. Notice the social and economic impacts (pages 5-9) address each of the four criteria in turn.

The body of the report is only 10 pages. The remaining pages are Annexes, for those who need detail. Here you’ll find the four case studies, the survey analysis, economic analysis, and more information about the evaluation design and methods.

You can download the report here

King, J., Arau, A., Schiff, A., Garcia Aisa, M., McKegg, K. (2022). Social and Economic Impact Assessment of the RCA Programme: Non-Destructive Testing Case Study. International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna.

We also completed two other impact assessments, on radiotherapy and crop mutation breeding respectively, using the same general approach:

King, J., Arau, A., Schiff, A., Garcia Aisa, M., McKegg, K. (2022). Social and Economic Impact Assessment of the RCA Programme: Radiotherapy Case Study. International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna.

King, J., McKegg, K., Arau, A., Schiff, A., Garcia Aisa, M. (2020). Social and Economic Impact Assessment of Mutation Breeding in Crops of the RCA Programme in Asia and the Pacific. International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna.

JK&A, 2022