Scaling return on investment

I am often asked to assess return on investment (ROI) from a pilot. However, ROI of a pilot is not a valid indicator of potential ROI at scale. For example, some pilots don’t show a positive ROI but may be a worthwhile investment when scaled up.

With a bit of care, we can unpack that value and draw important intel from pilots that helps determine potential ROI at scale.

What is ROI?

ROI is one indicator that comes out of a cost-benefit analysis (CBA). This term is also sometimes used colloquially as a catch-all for other indicators from CBA, such as net present value, benefit-cost ratio, and internal rate of return.

All of these indicators help us to assess whether an investment in some activity such as a policy, program or intervention creates more value than it consumes. When we do a cost-benefit analysis (CBA), we are comparing value created (benefits) with value consumed (costs) to see if an investment makes society better or worse off overall.

A scenario

Imagine we’re piloting an approach to help people whose jobs have been displaced. In a changing world, some people find the skills they have used to earn a living are no longer required. Some are at risk of experiencing long-term unemployment. Our pilots aim to help them re-skill quickly and enter new job markets where there’s growing demand and a shortage of workers. We will run four pilots, each developing and testing slightly different approaches.

Our pilots involve brokering relationships with members of the displaced workforces, prospective employers, and industry training organisations, with a view to connecting the right employers with the right trainees. Costs include running the brokerage service, and a funding pool to subsidise entry to training. Benefits will (we hope) include faster return to work, and improved labour market efficiency (reduced structural unemployment).

Funding comes from a philanthropic grant, and the donor wants to know: what’s the ROI from the pilots? This seems a reasonable question to ask, and we can understand the donor’s reasons for asking. But it’s been my experience – across multiple pilots, in diverse settings – that beneath the surface, there are often a couple of subtly different questions that can yield more useful answers:

- Is the pilot providing value for money?

- Is the pilot worth taking to scale?

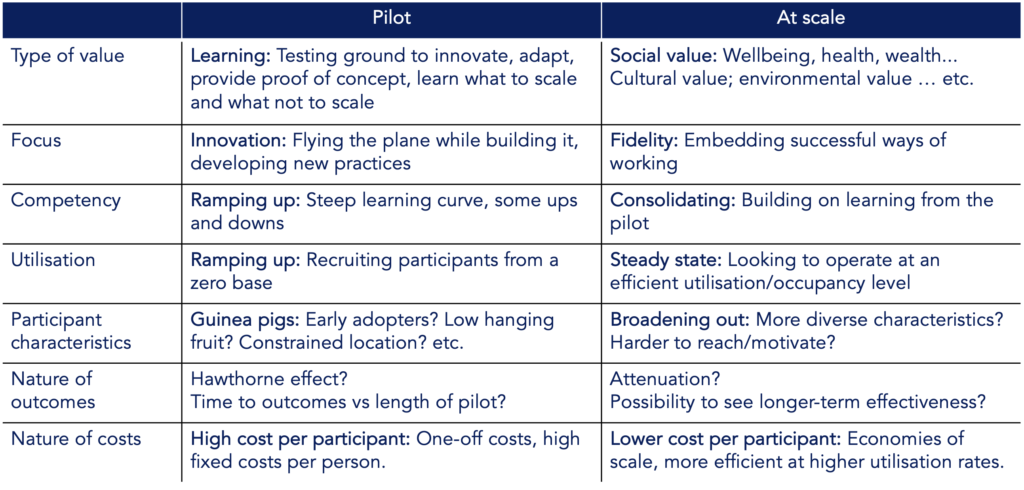

However, a pilot and a full-scale version of the same intervention create value in fundamentally different ways.

The value of a pilot comes from being a (relatively) modest investment in a testing ground to innovate, adapt, learn, and provide proof of concept. Our pilots, if successful, will improve outcomes for a small, one-time cohort of participants. However, the principal value of the pilots is the learning that might lead to a sustainable, scalable approach. The key focus of the pilot should be “what did we learn?” and ensuring we get maximum value from this learning.

The value of learning doesn’t translate easily to ROI. For example, pilot A might be highly effective and represent a viable model for scale-up. Pilots B and C might show mediocre performance overall, but might pioneer distinct elements of good practice that can be combined at scale to make pilot A even more effective. Meanwhile pilot D might turn out to be nice in theory but unworkable in practice (“a failure”) – and this, too, is valuable learning because we have learned something about how not to spend resources in scale up. Pilot A could show a positive ROI; Pilots B, C and D might all fail the ROI test – yet all have been valuable in different ways.

More insidiously, ROI of a pilot might not predict ROI at scale. Pilots differ from a full-scale programme in important ways that can affect their ROI. I have seen plenty of cases where a pilot’s costs exceed its benefits (so it could be written off as a ‘poor investment’), yet if we more carefully unpack the results of the pilot we find benefits are likely to exceed costs at scale. This might seem paradoxical, but it really isn’t, if we consider some of the differences between a pilot and a full-scale approach…

- The pilot and the programme are doing different things: During a pilot, we’re often ‘flying the plane while we’re building it’, learning by doing, and developing new practices. In contrast, if and when we scale up, our focus will shift to embedding successful ways of working. The pilots don’t reflect a single way of doing things that remained constant for a period of time, but rather a situation that was constantly in flux. The outcomes of the pilot might not represent potential effectiveness at scale.

- Different operating environments: For example, suppose our pilots are set up as short-term projects, with staff and office space hired on a temporary basis. In contrast, when we scale up we will be looking to partner with large-scale organisations with existing offices and staff nationwide. These organisations should be able to adopt new practices at relatively low cost, using existing resources to do things differently. The costs of the pilot might not represent potential costs at scale.

- Economies of scale: Even if the operating environments of the pilot and the full-scale approach were similar, the costs of delivery often reduce with scale. The pilots are small – working with 25-30 participants each – so that we can move quickly, try things, learn, adapt, and try again, all at relatively low risk and cost. However, this means that our fixed costs, i.e. costs that are scale-independent such as some overheads, are spread across a small number of participants – so the average overhead per participant is relatively high. In contrast, when we scale up we might work with thousands of people each year – so the average fixed cost per participant will be much lower.

- Ramping up: Compounding the effect on average cost per participant, the pilots won’t be working at full capacity from the start. Initially they will start recruiting participants from a zero base, and may take several months to ramp up to their full capacity. Therefore participant volumes will be lower, and cost per participant will be higher, than they would be in a steady-state system.

- Characteristics of participants: Circumstances and needs of the employers and trainees who opt in to the pilots may differ systematically from the larger pool of people and organisations that we hope will participate under a full-scale programme. For example, early adopters may represent ‘low-hanging fruit’ who are more open to change and more motivated than the wider target group. If we’re only working with one industry group, characteristics of participants may differ when we expand into other industries.

- Hawthorne effect: Pilots are famously susceptible to the Hawthorne (observer) effect; project staff and participants know they are being watched, so they try extra-hard and get amazing results that prove harder to achieve in an ongoing, full-scale programme.

- Length of time to outcomes: We only have pilot funding for (say) 12 months. We think this will be long enough to see some positive effects for some people. However, it will take longer before we know the full effect of the intervention and whether effects are sustained longer-term.

For all of these reasons, ROI of the pilots is pretty meaningless as a predictor of ROI at scale. Ultimately, pilots will meet their value proposition if they provide learning that informs future endeavours, and the ROI that matters is the ROI of successful approaches at scale. And, when the time comes to evaluate ROI at scale, the pilots are a sunk cost, having already discharged their function, so are excluded from the analysis.

But don’t get me wrong: pilot costs and benefits hold important clues about what costs and benefits might look like at scale. Instead of considering pilot ROI (costs and benefits in the aggregate), we should instead analyse pilot costs and benefits separately, consider how each might change from pilot to scale-up, and then bring them back together to assess ROI at scale.

For example, pilot costs can be disaggregated into ingredients – components such as staff, offices, equipment, and operating costs. We should also separate the pilot’s establishment (one-off) costs from its recurrent (ongoing) costs, and separate fixed (scale-independent) from variable (scale-dependent) costs. We should unpack the cost drivers (units of input or activity that cause costs to vary – e.g. number of staff, number of workshops, etc) and unit costs (e.g. cost per staff member, cost per workshop, etc). Then we can define what the service will look like at scale, and reassemble the cost data to estimate the costs at scale. Similarly for benefits, we need to examine the results of the pilots and consider whether we can expect the same sort of effect at scale, or whether some adjustments are needed (e.g. for demographics, timing, Hawthorne effect, etc).

We won’t know the precise values of some variables. But we probably have a reasonable idea of the range of possibilities. One of the great strengths of CBA is that we can play with a range of values for input variables to see how they affect the results. You can read more about sensitivity analysis, scenario analysis and breakeven analysis here.

If you’ve read any of my other posts, you’ll know that I view ROI as an indicator – and like any indicator, ROI can tell us something important but it’s not the whole evaluation. For example, our pilots might create value by improving equity of outcomes for disadvantaged populations at heightened risk of long-term unemployment. Economists have experimented with ways of incorporating equity in CBA, but your everyday, run-of-the-mill CBA is a method for evaluating efficiency, and questions of equity are set to one side.

In summary, pilot ROI is a poor and misleading predictor of ROI at scale – but pilots can provide important clues about the nature and structure of costs and benefits at scale, and can inform careful and thoughtful analysis of potential ROI at scale.

Also see my Substack posts on cost-benefit analysis:

- Cost-benefit analysis and the logic of evaluation: CBA can be understood as a form of evaluative reasoning, demonstrating it belongs to the field of evaluation as much as it does to economics.

- Social Return on Investment vs cost-benefit analysis: Similarities, differences, and opportunities to improve practice of both.

- Modelling costs and benefits in uncertainty: Three easy uses of CBA to clarify implications of uncertainty and support better decision-making.

- Cost-benefit analysis through an evaluative lens: Harness the unique strengths of this important evaluation method and mitigate its limitations.

- Contextually-responsive CBA: What would it look like to conduct CBAs that are inclusive, responsive, contextually viable and meaningful for people whose lives are affected?

December, 2020 / Updated July, 2023